Selling data for fun and profit: an introduction to data businesses

I recently read an excellent piece by Auren Hoffman, titled the ‘Data-As-A-Service Bible”. Here’s a link to the article.

This piece is mainly a summary of Auren’s ideas. But not entirely.

I tend to summarise a lot of articles, normally by filtering for important points, and then expanding on them. But every point in this article felt important. Probably why it was a 32 minute read.

The article calls itself a bible. It’s appropriate, I think, because the Bible is also hard to summarise. Here’s the Bible in a sentence: a guy called Jesus, who was God’s son, died and came back to life. It’s correct, technically, but also misses a whole lot.

So this might be a long one. Here goes.

What is a data business? Link to heading

A data business sells data, usually to companies.

Data is sold as a service, meaning the customer pays for what they use, with limited commitment and a variable pricing model. There’s a variety of ways this could work: a subscription per-month model, a once off, a per-head model. So a data company is also called a DaaS (data as a service) company.

Data businesses are not really comparable to SaaS (software as a service) businesses. There are similarities, but also big differences. Treat them as their own entity.

Who buys data? Link to heading

Historically, companies didn’t often purchase data from outside sources. Most of them struggled just using their internal data. In addition, companies currently have many more software partners than data partners.

There’s still not that many data buyers now. Companies want solutions, not data. Yet there’s still an order of magnitude more data buyers now than 5 years ago.

So it’s changing, and changing fast. Companies are more and more likely to look for external data sources to complement or replace their internal data sources. It’s a good time to get into the data game, particularly if you think the number of data buyers will keep increasing.

What companies buy data? Firstly, data buyers are likely to be other technology companies. These businesses are sophisticated enough to get value from external data.

But it’s not just tech-savvy companies who want data. More traditional companies also want data, and a company like Starbucks is one example. Starbucks probably would struggle to attract good data engineers. Yet with tools like Snowflake now available, they might not need them. Suddenly they can handle data, and suddenly they can buy data.

One way you can find customers is by looking at the tools they use. Companies using tools like Snowflake or Looker probably want data to use with those tools. This also applies to customers using something like BigQuery.

The four quadrants of data businesses Link to heading

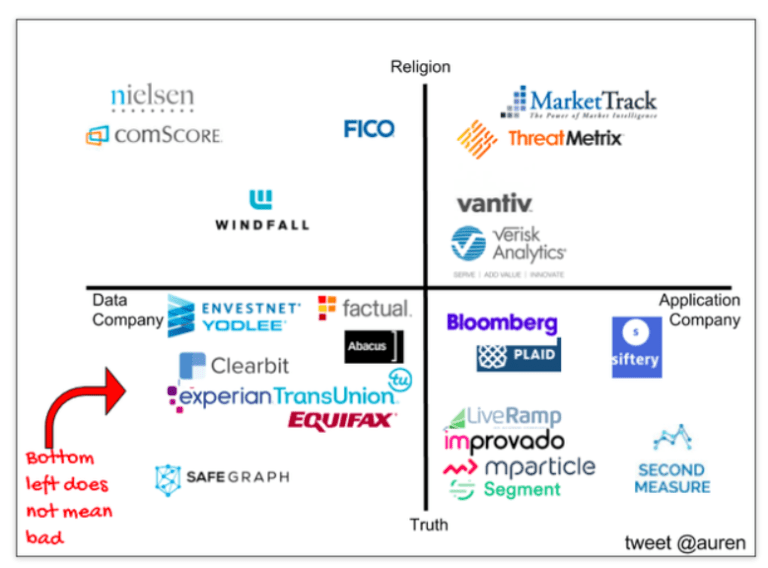

One useful framework classifies data businesses into one of four quadrants. This is how they score based on two axes: religion vs truth, and application vs data.

Truth companies focus on collecting facts about the past, and getting them right. A truth company is judged primarily on its data quality and they tend to have a lot of data engineers.

Religion companies try to predict the future, usually through predictive analytics or machine learning. These companies seem to compete mostly on brand, and are judged primarily on their market perception. They tend to have a lot of data scientists.

Data companies sell data, and that’s all they do. They don’t have a user interface, they don’t build applications, they just sell data.

Application companies use data to build pretty web applications for end users. They have nice user interfaces but need data to make them work properly.

How do these relate to each other? Truth companies sell to religion companies. And data companies sell to application companies. Religion and application companies make their money in other ways.

What types of data are there? Link to heading

There are a few common data themes.

Data about people. Examples: email address, driver license number, address, phone number, advertiser ID, cookies, name.

There are significant privacy issues to be aware of when collecting people data. After all, data regulations make up a significant part of privacy law. These privacy issues can make it difficult to work with people data, but can also make it a competitive advantage, since it acts as a deterrent to all parties.

Data about products. Examples: barcode, where they sell, what they sell for, price history, dimensions, serial number, materials used in manufacture distribution.

Product data can be niche. Think a wine intelligence business selling data on wine bottles, or a business selling everything related to cars.

Data about places. Examples: maps, store hours, addresses, time of visits, geometry, category of place, traffic, ip addresses, real estate rentals, residential property

Data about companies. Examples: stock prices, name/address/histories, privacy policies, news articles

Data about procedures. One example would be data about the Lasik eye surgery procedure: how it’s done, safety regulations, success rates, stories of success and failure, odds, doctors who do it, time, equipment, expertise.

How do you get data? Link to heading

There are a few common ways to get data.

One is to make agreements with companies, where they give you their data in exchange for analysis over the data. Another is to harvest public data, which could involve web scraping, REST API’s, or collecting data by hand (e.g. with call centres). A third way is to try and buy it from a company, but companies tend to value their data highly, so this can be an expensive method.

With data businesses, the cost of data will exceed revenue initially, since your model is to get the data once upfront and sell it multiple times. You’ll need some time to make a profit.

But the good news is that the data assets you build become exponentially more useful over time. It’s a business model that works similarly to compound interest, in that you need to stay long term to see the benefits. It’s a model with slow growth initially and strong growth in later years.

Establishing market share Link to heading

Data companies grow their market share by being cheaper or better than their competition. As their market share goes up, they can put their price down, which grows their market share more. It’s a cycle. But how do you start it off?

One way is to focus on a niche in the market. Eventually you’ll need more niches, but the first one buys you time. Another way is through aggressive pricing, like Amazon’s model. This can be done because it’s usually cheap to acquire data.

Alternatively, you could also acquire someone else. Acquisitions are easy for data businesses. You’re just putting data together, or merging your products and offerings. That’s not that difficult.

Data must be useful and reliable Link to heading

Firstly, data accuracy is the most important thing for a data company. Customers need to be able to trust your data. It’s so important that, to assure their customers, some companies even publish their accuracy improvements online.

Secondly, you should collect data with a common theme, like people data or places data. This has a few benefits.

One is accuracy. There’s an implicit tradeoff between data accuracy and data coverage. The more you cover, the more you have to check, and the less likely you’re right about every area.

Collecting data with a common theme is also useful because you’ll get datasets compatible with each other. With this data there’ll be join keys you can utilise, such as UTC standardised time, an address or a postal code. Data across many topics might not link together at all.

Think about what questions your data answers. The reason data is useful is because it can answer questions. The more datasets you collect and link together, the more questions you can answer, and the more valuable your data becomes. Each customer looks for data to answer a question. You want your data to answer as many questions as possible.

So if your data is across themes, you’ll answer less questions and get less customers. If it is targeted, you’ll attract interested customers, since your data can solve their problems, and your data will be more accurate too.

What else? Collect data with a time dimension. Again, this has benefits.

Data with a time dimension tends to be interesting data, particularly if it changes a lot over time. Customers can’t rely on a once off data dump since they’ll miss out on new data. So they’ll sign up to a subscription style model, where they’ll buy data from you over a period of time. Subscription models are useful since customers interact with you multiple times. This makes them more likely to remember your brand and buy from you again.

Make it easy for your clients Link to heading

It’s all about the client. Make your data as easy to use as possible to the customer, and they’ll keep coming back. Data you can join to other data is valuable data, and data you can’t join isn’t. It’s that simple.

The customer must be able to join their data to your data. How? Through a common column, or key. This might be something specific to a customer’s data (easier to arrange if you’re small) or something that is commonly used.

The SIMPLE acronym for a good key Link to heading

- Storable: key can be stored offline easily

- Immutable: key doesn’t change over time

- Meticulous (high precision): the key always refers to the same thing. This needs to be across systems, including systems you haven’t seen before. For example, your TFN is unique to you, or your ABN is unique to your business.

- Portable: key can be moved easily across systems

- Low-cost: key is cheap or free

- Established (high-recall): key covers a lot of the population

Sometimes you sell data that relies on some other data to be useful. Make sure your customers also have the other data. For example, if your data is useful alongside Australian census data, you could give the customer both your data and census data. Make it easy for the customer to use your data.

What else makes it easy for the customer? There’s a few supporting documents that will help both them and you:

- A data dictionary, with the names of the columns and what each one means

- A document listing any data transformations you’ve done, such as deduplicating, UTC time conversions or missing value imputations

- A document with a list of assumptions of the data, like “only one of these two columns can take a value” or “this column depends on Australian Census data”

How does your customer get your data? There’s many delivery options, like an API, s3 storage, csv files, and so on. Just note this: customers want to try your data before they buy it. It is critical that you make this as easy as possible for them. You could have a freemium model, where you give them some data with the promise of much more when they pay. Or you could have a self-serve model, where the customer could look at data themselves using a web interface.

You can upsell to happy customers. If you are reliable, if the customer likes what they see, then they are more likely to buy from you again. The products you upsell, though, must have the same high quality. You’re better off not upselling than giving the customer something bad.

Protect yourself Link to heading

The most common way of protecting your data assets is with a data agreement.

A data agreement is a contract between you and the customer that specifies what they can do with the data. For example, they could stop resale of the data by the customer, or specify the data must be deleted after some period of time. Data agreements are common, but complicated, so have a lawyer draft these. It’s also a good idea to standardise them across customers, since it’ll take some time and effort to customise one for each customer.

It’s easy to copy data, so a customer might do it anyway and claim they didn’t. How could you prove the data was yours?

One way is to add a watermark to your dataset, like a few fake rows of data. For example, mapmakers might add fake streets into their maps, so if they see a map with those streets they know it’s theirs.

You could also do a different watermark for each individual customer. Then, if you find your data has been copied, you can see what customer took it.

Finally Link to heading

Starting a data business is a long road. Ensure you’re fully committed before you start. But it could very well be worth it.